Why is med school pre-clerkship curriculum so poorly designed?

With students largely using online 3rd party resources for the content, schools need to focus their in-class time on clinical skills

Sorry for the delay in posting. Hopefully I make it up with this one - it is quite the manifesto.

As a third-year med student whose clerkships will soon draw to a close, I took some time recently to reflect on how different this year felt compared to the first two. It makes me grin remembering that first week in my first rotation in Family Medicine where I was thrown into the pool of a high-volume clinic and was forced to sink or swim. One thought I couldn’t quite get out of my mind was how poorly the pre-clerkship curriculum was in preparing me for the demands of this year.

Although I had a strong grasp over the actual content of medicine and had successfully passed Step 1 - I completely choked during my first real encounters. I had no idea what exam to conduct, what questions to ask, and how to best optimize the limited time I had during visits.

This experience perfectly encapsulates my criticisms of the current model of medical school pre-clerkship education. I realized that it didn’t matter if I knew that amyloid showed up as apple-green birefringence on a Congo Red stain. It did not matter if I knew all of the enzymes in the Krebs cycle.

That is because I realized that the one thing an M1 or M2 needs to know before hitting the wards is how to take a good history and perform a focused physical examination. You learn over the course of your M3 year to synthesize this information to develop a differential diagnosis and build a plan. That is the essence of learning clinical medicine and is how you train to become a good future-physician.

Instead of providing ample experience to build these important skills, much of the M1 and M2 curriculum in many American medical schools largely focuses on drilling board-irrelevant factoids into our heads through days of lectures, testing us with poorly-written assessments, and spending large amounts of time dissecting in the anatomy lab. I will discuss in this article how the medical education landscape has rapidly changed over the past decade and why this model of curriculum has become antiquated.

So let’s now discuss specifics about how pre-clerkship curriculum is generally designed and how it can be reoriented to not only fulfill its true goals and save both the school and students time and money.

In my strong opinion, the pre-clerkship curriculum should have two goals in mind:

Preparing students to pass the USMLE Step 1 - this is a difficult and broad exam testing the basic sciences of medicine, and is the single largest hurdle in medical school. Students should be prepared to take the exam before clerkships begin. Taking this exam in M2 year clears the path for M3 students to focus solely on clerkship learning and Step 2, which is where they truly learn the practice of medicine. Juggling post-clerkship content along with Step 1 content adds significant stress and can hamper post-clerkship learning.

Teaching and reinforcing clinical skills before they hit the wards as a third-year - students need large amounts of clinical experience, either real or simulated, before their real clerkships. Elevating the baseline clinical level will help students gain the most out of their rotation experience. This is where real medical school starts. Also, with Step 1 going pass-fail, clerkship performance and preceptor comments are becoming a larger metric to judge candidacy for residency.

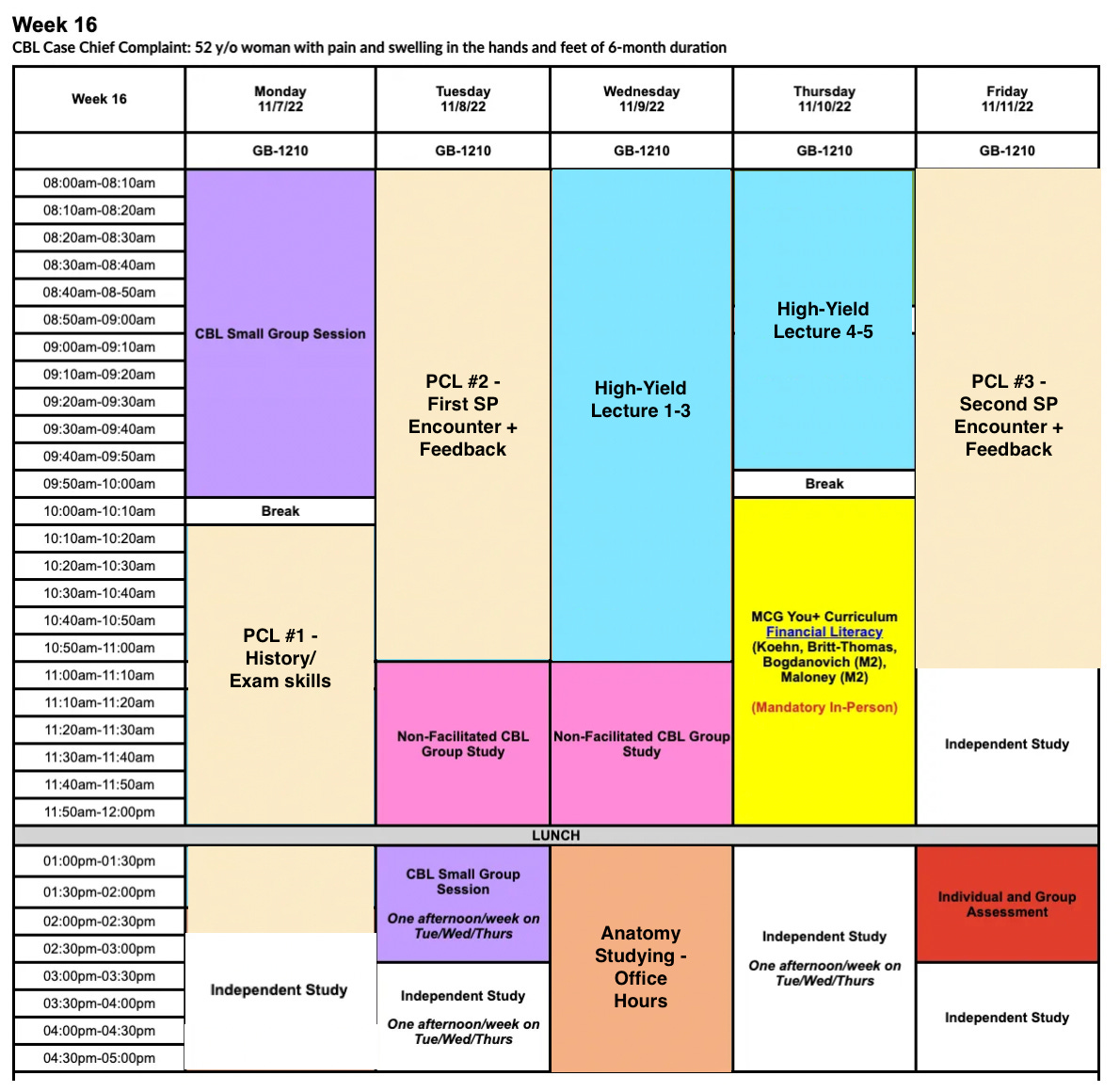

Now let’s look at an example of the average week of M1 or M2 at my medical school. I cannot speak for all medical schools, but most schedules at other schools will look largely similar. This is due to standards set by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which all accredited medical schools in the US follow.

Firstly, let this not be considered a criticism solely of my alma mater - I am extremely fortunate to study here and I think that I received a very strong education, but at the same time there is certainly room for great improvement. Like I just mentioned, our curriculum follows the general design followed at most American medical schools. In essence, I am critiquing the design of most medical schools in the US.

In this chart, the blue represents content lectures, the purple and pink represent small-group case-solving sessions, orange represents anatomy dissection sessions, and green and yellow represents lectures on the “humanities of medicine.” The beige represents small-group physical examination learning and simulated patient encounters where students practice seeing patients, giving oral presentations, and writing notes. The end of the week concludes with a quiz covering the week’s material.

Out of the 41 hours (excluding lunch hour) depicted on the schedule, a whopping 16 hours are devoted towards content lectures or anatomy, 7 hours are devoted towards case-based learning, and a pitiful 4 hours are devoted towards training in clinical medicine. With this distribution and the fact that scores received in clinical skills training were not counted in our grading system, you can imagine the direction that student priorities went.

So you might be thinking - well, there’s a lot to learn in medical school right? Does it not make sense that most students spend most of their time in lecture? Yes it would - but in fact, much lecture content contains vast amounts of board-irrelevant content and assessment questions at the end of the week were composed by the lecturers themselves. Unlike college, where you may have one professor teaching a class the entire semester, in medical school, nearly all lectures are given by different faculty. Many of these lecturers give only one or two lectures a year on one topic, are not physicians (and never took Step 1 themselves), and have little knowledge on NBME question-writing or the material that is high-yield on the Step 1 exam.

As a result of this model, lectures were wildly inconsistent, ranged anywhere from 50-150+ slides and varied in quality and style of content delivery. The same went for assessments, where question styles also varied widely and did not undergo quality assessment or standardization before being administered on exams. From personal experiences of talking to peers at other institutions and reading forums online, I was surprised to learn that many students feel the same way around the country.

It became painfully apparent to many students within the first semester of medical school that they would need to study large amounts of extra content outside of school in order to prepare for Step 1 and to answer their distinct style of questions. In our already-constrained weekly schedule, my peers and I found studying for school assessments and the Step 1 exam largely antagonistic to one another since they contained little overlap.

For example, one week we received an hour-long lecture and 3 non-NBME style quiz questions on one condition - osteochondritis dissecans. You will never see this tested on USMLE Step 1 and while it is bread and butter for orthopedic surgeons, 95% of students will likely not see this more than a few times in their entire careers. This is a great example of a topic that may be relevant to teach during an ortho grand rounds presentation, but not for an M1/M2 curriculum with different goals. There is simply not enough time to cover every obscure disease or the bread and butter in every single subspecialty - time that should rather be spent covering the basic sciences content tested on the Step 1 exam.

As a result of this design, in a class of 200+ students, only a small fraction incorporated lecture content in their regular studying and only about 5-15 students actually attended lecture on a regular basis. Most students elected to ignore lectures almost entirely.

One might say I am putting too much emphasis on the Step 1 exam and that content tested on the exam is somehow more relevant to our careers than whatever medical school teaches. I disagree. Many have correctly raised valid criticisms of the content and question-style of the USMLE exams, which I can certainly write another post about. However, it still doesn’t change the fact that without passing this difficult exam, you will never become a doctor in the US, even if you otherwise did well in medical school.

Anatomy in particular was another large time-sinker. The MSK system comprises 6-10% of the Step 1 exam with only a small fraction of those questions actually devoted to gross, non-clinically corellative anatomy, yet most medical students nationwide spent 3-5 hours weekly for at least 1.5 years dissecting and countless hours outside of class to study anatomy for lab practicals. I think it is important for medical students to study anatomy in school, but there is little value in having students actually dissecting as a way to learn. I always would have opted for a prosection-based curriculum, where students study pre-dissected cadavers.

In fact, studies have found no difference in anatomy exam performance between a dissection vs prosection-based curriculum. Hours of time spent in active dissection could be redirected to study board-relevant content or undergo additional clinical skills training. This has been a subject of debate over the past several years, especially as the COVID pandemic forced medical schools limit in-person schooling for several years. A few schools have begun to catch on and have started switching their anatomy courses to prosection.

Overall, this undue emphasis on non-NBME content and dissection-based anatomy is also not up to date with how most medical students organize the material and study for the Step 1 exam these days.

In recent years, third-party resources, such as pre-made Anki flashcard decks, Boards and Beyond, Pathoma, Sketchy Medicine, and Amboss have surged to dominate pre-clerkship studying. If you walk around our library after class ends, it is difficult to walk around and see a medical student not tapping away at their bluetooth game controller finishing their daily Anki flashcards. Many students have found a preference for these resources over traditional class lectures as they largely comprise of small 10-30 minute videos that teach extraordinarily well and break down the basic sciences content into the most clinically-relevant and board-relevant pieces. These resources give students consistency in teaching style and prep students based on what they will expect to see on the USMLE exams. A 2022 AMA survey found an astonishing 70% of students using these resources on a daily or weekly basis in school.

Despite simply the saved time, using these resources in addition to Anki emphasizes the use of spaced active-recall to learn and retain material. When preparing for a test like Step 1, there is no room to forget any material - you must be just as proficient in the last topics in the last module as the first topics you may have learned on the first day of medical school an entire 1.5-2 years earlier. With each traditional lecture containing anywhere from 50-100+ slides, there is simply no way to optimize this for a reasonable study plan. Anki solves this problem. Using algorithms, each flashcard you answer correctly increases the delay in time until you see that flashcard again in your daily rotation while answering incorrectly resets the time delay for you to see the flashcard again sooner. This filters out content strengths and weaknesses for you so you spend the most time daily on content that you are weak in. By “offshoring” the organization of the vast amount of study material, students can spend more time actually studying.

The differences between mainstream methods for studying medicine in 2024 compared to anything I had studied previously was shocking. As a very traditional lecture-based student my whole life, I was initially resistant to using these novel resources and strategies. However, I sincerely believe they were the driving factor in me being able to take Step 1 before M3 began. I genuinely believe I would not have learned medicine as well if I did not adapt to these novel methods. The vast evidence surrounding active-recall as the best studying strategy also cannot be denied.

It boggles me that schools have entire committees full of staff devoting significant time towards designing a curriculum when all of the content that is covered on the Step 1 exam is already identified and organized well. All of the hard work has already been done! Instead of trying to re-invent the wheel, we need to begin focusing on getting with the times and integrating these third-party resources into school-specific curriculum, as these resources are here to stay and continue to grow even more popular every year. We must think of a curriculum framework outside of the bounds of an archaic lecture-based content delivery system.

The same can be said about in-house exam design. UWorld and Amboss, among other question banks, have already done the hard work of creating thousands of NBME-like questions that are considered the gold standard prep for Step 1. Medical schools also have access to actual NBME question banks with thousands of retired Step 1 questions as well. With all of this in the palms of their hands, why expend additional resources for underqualified and underinvested faculty to create new questions that do not mimic their style and do not cover the same content?

The largest hurdle in all of this is the cost of these resources. While Anki decks are free, each of the other resources I mention will run a bill of a few hundred dollars each. Yet as students, we pay tens of thousands of dollars and rack up significant debt yearly for these medical schools to teach us and assess us the wrong way. Medical schools should dial back on the resources that go into setting up our 16+ hours of weekly lecture and low-quality in-house assessments and instead provide these resources to us at a subsidized rate or ideally, free of charge. If they cannot provide these resources within the budget of our large cost of attendance, then difficult questions need to be posed.

Why medical schools continue to teach the same way for the past 100 years, I couldn’t tell you. I think there is simply a large disconnect between faculty teachers and this new generation of medical students who have broken free of the studying methods of the past. I had a recent conversation in passing with a faculty member on the committee that designs our pre-clerkship curriculum. When I asked if they were familiar with these overwhelmingly popular third-party resources, they had no idea. I sat down with them and explained how they work, but it was surprising to see the how these influential faculty were so out of touch with our class.

Medicine is also a career that respects tradition. We are often times reluctant to let go of old methods, claiming that it is all part of the process, but we have absolutely no data showing that our current model of education is the best for educating our future doctors. I have a high degree of suspicion that it is not. Just like we have changed the actual practice of medicine with new advancements and trials, we should do the same with medical education and rigorously study it for opportunities to improve current methodologies.

Now let’s talk more about the clinical education aspect of medical school. In our school, it is known as Patient-Centered Learning (PCL). This was by far the most useful aspect of medical school in preparing me for M3. At its core, it resolves around learning relevant interview and physical exam techniques along with conducting simulated patient encounters with standardized patient (SP) actors. After these encounters, we present our patient, write a note, and receive 1-on-1 feedback from our preceptors covering every aspect of the encounter. Now for SP ecnounter PCL sessions, a student does not need to be present the entire 4 hour block. They will be required to be present for the entire encounter and feedback session (usually ~1 hour) but can go home and study for the remainder of that time. The time blocks are allotted this way as there are a limited amount of SPs, preceptors, and exam rooms so not everyone can have an encounter and receive feedback at once.

These sessions are organized to align with the current phase of the curriculum, so if students are in the cardiology/pulmonology module, they will learn the cardiovascular exam in that month’s PCL and the chief complaints of the SP will be chest pain, shortness of breath, leg swelling etc. This is my favorite aspect of how PCL is designed - learning the clinical presentations for conditions that you are also learning the pathophysiology for in school can help solidify all aspects of a particular disease state.

But like I described earlier, PCL is conducted in one four-hour session every week. At a monthly view, we would have roughly 2 learning sessions and 1-2 standardized patient encounters + feedback. If we do some math here, I estimate we likely had 18-40 true encounters before our M3 year began. This is wildly insufficient and likely contributed to my feelings of unpreparedness during my first rotation.

Due to PCL assessments not counting as true grades and the strain on our schedules studying antagonistically for both school and Step 1, most students simply wanted to collect their “pass” and go home so they can catch up on the 4 lectures given that morning. I suspect a similar attitude was adopted at most institutions. In our M2 year, we averaged about 1-2 PCL sessions a month with perhaps 1 SP encounter with feedback. This is a completely wrong direction to take the curriculum.

If it were up to me, M1s and M2s should be doing at least 2 SP encounters per week, all graded. This will result in about 140 simulated encounters in a 1.5 year pre-clerkship curriculum and almost 200 in 2 years. This includes oral presentations and full notes. Once we get to the half year before clerkships begin, we can start introducing assessments and plans into the PCL experience so students get adequate practice in this respect before M3, where they will be expected to do this for all of their patients on a daily basis.

Breaking this down into a weekly curriculum design, I would like to see a minimum of 3 PCL sessions weekly, with the first devoted towards training in history and physical exam and the remaining two as formal SP encounters with feedback.

A short word on assessment - I don’t necessarily think that PCL should be the largest proportion of your grade in school. Of course, there is preceptor-dependent subjectivity that goes into PCL and the fact that different students can progress at different rates. A student interested in pathology or radiology and who did not enter medicine to necessarily examine and interact with many patients on a daily basis may be a bit weaker than someone interested in outpatient family medicine. And that’s okay. However, it should be enough so that their skin is in the game and that they are incentivized to do well and seek improvement. For many who struggle with the fire-hose of medical school content but are strong in a clinical setting, this may actually be a way to increase their grade. I estimate 10-30% of PCL counting towards overall grade is fair to accomplish this goal.

One common pushback I have experienced is that SPs are paid, trained actors hired from the community and that increasing the frequency of encounters will cost additional time and money. Once again, given the fact that we pay tens in thousands of dollars in tuition yearly and that clinical skills are the most important proficiency that medical school can teach students, can someone tell me a higher priority for our tuition?

So putting all of this together, I created a modified schedule. Let’s see how it looks like:

With this approach, we drastically reduce lecture time to twice weekly with a total of 5 hours. These lectures comprise high-yield topics that align almost entirely with the third party resources students use out of school to study the week’s content. I argue perhaps this is not even required - schools can instead just identify the sections/chapters of Pathoma, Boards and Beyond, and Sketchy that will be covered that week so students can prepare on their own. Questions for assessments should be sourced from reputable question banks instead of faculty-written and vetted to ensure compliance with USMLE-style.

Now I know that there are students who prefer learning the traditional way with in-house lecture material, even if it includes board-irrelevant content. For these students, lectures should be pre-recorded and put in an online repository so that they can access them at any time. While students should always be encouraged that this material is nice to know and to watch if they are interested or have time, the emphasis on exam material should be from board-relevant content. For example, there should be no questions on content covered strictly in a traditional lecture that was not covered in a high-yield lecture or in the recommended third-party content in the week. This strategy also eliminates the funds, resources, and time that it takes to organize the same traditional lecturer to give their one yearly board-irrelevant lecture over and over again. Have them give it once and keep that lecture in the online repository for successive years until it becomes out of date.

We also remove anatomy dissection time and replace it with anatomy “office hours” where students can study prosected cadavers with on-site lab staff and tutors. Students are also free to visit the lab off-hours to study on their own. This essentially does not change the studying strategy of anatomy - most students don’t learn the anatomy during active dissection anyway, and most points on the practical are obtained through coming into lab off-hours to review structures.

Case-based learning has been modified slightly to 2 sessions per week and there is still time on Thursdays for the humanities in medicine lectures. But most importantly, PCL is increased to three sessions a week, with the distributions I described earlier.

Overall, this schedule saves time for the student, who now gets out at 2:30pm one day, 3pm another day, maintains 1 afternoon off per week, and can choose between attending anatomy office hours or gaining another afternoon off and studying anatomy during off-hours (such as a weekend when there is no impending Friday quiz). It also intrinsically saves time by limiting lecture and assessment content to board-relevant material, which they are already studying on their own through third-party resources. Time is also saved because for PCL sessions #2 and #3, students only need to be there for their encounter and feedback time, not for the whole 4 hour block.

A final word on this redesigned curriculum. One criticism of this approach is that certainly shifts the responsibility away from schools and onto the students. This is true - it is up to the students to learn and keep up with the large amount of content themselves and put in the hours necessary to excel on the exams. Of course medical students, no matter the curriculum, should continue to be provided ample opportunities to get extra help and ask questions through office hours and review sessions etc.

But from what I have seen both at my own school and others, students are already taking on this responsibility and teaching themselves medicine with third party resources regardless of if their curriculum is adapting or not. They crave for the freedom from the system that they feel holds them back. Under the current model, our high Step 1 and Step 2 pass rates are an even greater achievement because they have been earned in spite of the current curriculum and not with its support. Furthermore, medical students are some of the best and brightest minds among their age-group. They can meet and exceed that standard, they just need to be given the best framework to do so.