Why the Med Student Research-Industrial Complex is not helping anyone

It drowns the literature in unimportant findings subsidized by unpaid labor and makes equity in medicine worse

As a medical student, it is almost customary to review the yearly Charting Outcomes report published by the National Resident Matching Program which describes the application characteristics of US MD seniors who successfully matched into their desired specialty. The entire 2024 report can be found here.

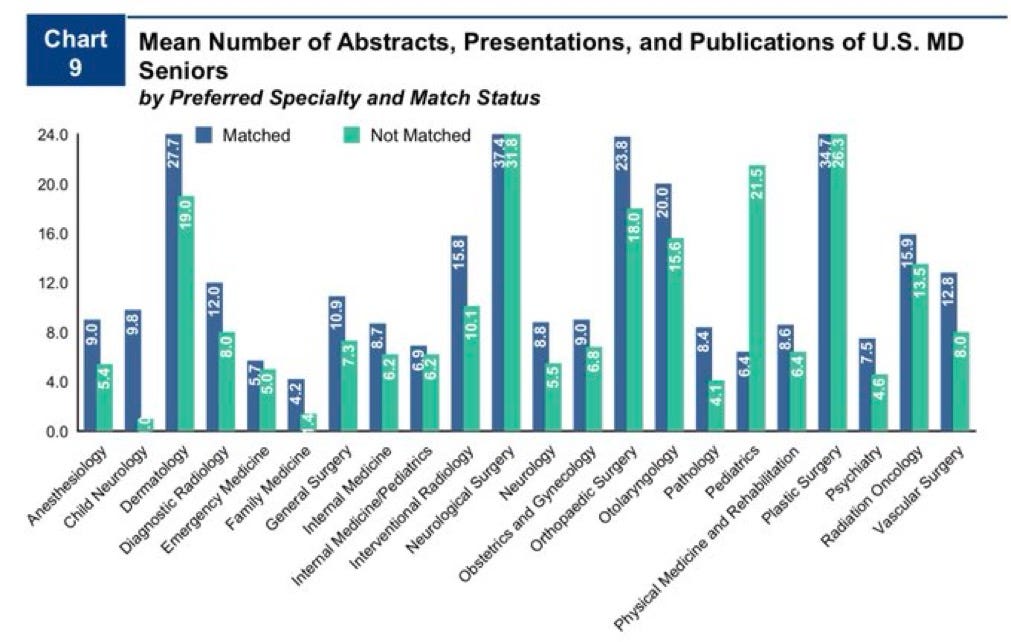

When this report released this year, my friends and I took turns making bets on the one page - the new numbers on average research products by successful applicants stratified by subspecialty. FYI, I put 35 on neurosurgery, 30 on dermatology, 20 on ortho, and 30 on plastics. These are astronomical numbers that would have shocked any match applicant a decade ago, but surprisingly, I was not too far off.

Lately, there has been an increased emphasis on medical students to get their name on various research products to stand out in residency applications. Take a look at the staggering numbers here.

Unsurprisingly, the highest numbers are seen among those applying to the most competitive of specialties - dermatology, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, and plastic surgery. As the number of interested applicants has grown both domestically and internationally but the number of residency spots has stayed largely the same, these numbers represent something of a “soft quota” for students to reach to have a reasonable chance of matching.

In some cases, the numbers in the green columns shocked me more than the blue. The average neurosurgery unmatched applicant had almost 32 research products - a staggering number that would have placed them in an elite tier of applicants for any other specialty. Yet, it was still 5 below the matched average, indicating that for some PDs, 32 was simply not enough. Time to take another year off in an already long and arduous training process to get their numbers a little better.

Now why is this happening? Largely in response to DEI concerns, medical schools have shifted away from grades and standardized tests in medical education. USMLE Step 1, pre-clerkship, and even clerkship curriculum in most schools has been changed to a pass/fail system. Many students these days go through all 4 years of school without once receiving a grade. It was already difficult enough to compare an “A” at one school to an “A” at another school, now residency program directors (PDs) have fewer tools in their arsenal to compare applicants on measurable achievements. As the data indicate, this has largely been supplemented with an emphasis on research output as the next best proxy. This is not a good idea.

Having a system like this encourages med students to not spend their limited time on studying, taking care of themselves, or participating in more meaningful activities. Instead, it incentivizes them to do the following:

Feign interest - students not interested in research have to pretend to be interested in academic medicine. Medical school should rather be place where students can engage with research to some degree, but more importantly, take time to figure out where their interests lie and how they want to practice. This means taking extra time to develop clinical skills and making decisions on academics vs private practice, urban vs rural environment, and hospital vs outpatient medicine.

Lock into a specialty early - Due to the unimaginable numbers in the table, students who may be interested in a competitive specialty need to commit early so they can do research in the topic. I’m sure most of the neurosurgery gunners on the chart took nearly the entire 4 years of medical school to get to 37. Say a student was interested in radiology but was inspired by their 2nd year shadowing experience or 3rd year clinical rotation in neurosurgery. If they want to consider switching, they are at a large disadvantage as they have limited time left to reach the research quota. Once again, there should be ample opportunities to explore and change specialties. I know many students who came in gunning for one specialty but completely changing their mind later on. Research quotas hamper this flexibility.

Conduct poor studies with unimportant findings - With limited time and few resources, it is unlikely that medical students publish anything of major significance or actually change the practice landscape. How many medical students worked on the TICO trial or PARADIGM-HF studies? Obviously zero. But that is okay - even if the findings themselves are not that important, it is imperative at this stage in their careers for students to learn good research practices and methodology and be able to recognize what makes strong research strong. However, implementing high research quotas distracts students from this goal and instead encourages them to answer obvious or unimportant questions, conduct studies with lax design to get the results they want, and publish in poor journals, all to get publications out faster. This experience to me is antithetical to how medical research should be conducted and is a bad influence especially on students who want to pursue academic medicine for their careers.

Engage in questionable behaviors - I have seen a phenomenon where students offer “swaps” to each other. “I’ll put your name on my abstract if you put my name on your case report.” This is simply gaming the system and boosting your numbers by doing no real additional work to no one’s benefit.

Gatekeep research from other students - At many places, including my institution, mentors willing to allow students to participate in research are small in number, especially for niche specialties. Well-connected students established in the sole group that conducts plastic surgery research are incentivized to not let other students join so they can maximize the group’s research for their resumes.

A brief note on the first point - I believe it is a competency for trainees and physicians to keep up with current research and engage in it regularly to shape their practice. However, I struggle to understand how participation in low-level research itself proves this. I would much rather have a doctor who reads NEJM and JAMA on a weekly basis than one who misses the bigger picture and spends all of their free time crunching out an extra low-impact paper in a predatory journal using poor methodology.

It is sad that all of this resulted from policy changes to address DEI issues, a valid issue that has plagued medicine for decades. However, I feel that the shift away from standardized tests has largely made this problem in medicine worse, primarily for specialties that already suffer from poor diversity. The main reason for this is the clear advantage that well-off students get when pursuing research opportunities in the first place.

It is an inherent privilege for students to take their summers off and to pursue unpaid lab opportunities in order to publish research. What about the student who is bagging groceries or driving Uber Eats during their breaks and summers to help pay their tuition? What about students who want to enter residency right after medical school to start paying back some of their extremely high college and medical school debt?

In this sense, a standardized test would be better. While I have certainly heard several criticisms toward our current medical licensing tests, their content coverage, and question style, it was for decades the only way to benchmark students across multiple schools and multiple backgrounds. While it is important to acknowledge that these exams had significant financial barriers, such as review books, tutoring, and Qbanks, this is arguably a smaller burden than the thousands required to subsidize a student’s unpaid dermatology research year or the exorbitant costs associated with publication fees.

These unrealistic research requirements only further increase the barrier for ultra-competitive specialties. What are we saying to a disadvantaged student interested in neurosurgery that in addition to an already taxing 7 years of post-grad training, they will likely have to do 1-2 more years of unpaid research as well? Neurosurgery already has some of the worst diversity of any subspecialty in medicine - the first black woman to complete the program at Johns Hopkins just graduated last year.

Who stands to benefit from this current phenomenon? I can tell you with confidence that it does not benefit anyone actually doing the research. Research to me is an exciting activity as I am strongly considering a career in academic medicine. But for most, the incentive structure has reduced it to merely “doing the time” so that a college student can get into medical school, a match applicant can match ortho, and a resident can match into their desired fellowship. The theme here is that research is no longer done out of a genuine curiosity to improve understanding or advance the field - rather, it has become a tool to climb up the rungs of a never-ending ladder. By the end of all this, someone may complete almost a decade of low-impact research to achieve their goal of working in private practice and never touch research again. I suspect this applies to many.

I can’t help but also recognize some sinister incentives here. Medical trainees are already one of the most overworked, debt-overloaded, and burned out class of employees, and making many of them take on additional unpaid research responsibilities to achieve their desired career does not seem like much of a fair bargain. One set of stakeholders who plan to benefit greatly from a system like this are our institutions, who can utilize this army of unpaid labor to increase their research output.

How should we fix this? The first step is quality over quantity. PDs should dive deep into applicants’ research records and consider the following:

Is there a consistent theme in their research? - This indicates someone’s genuine interest in a topic. Various low-quality publications on seemingly unrelated topics (unaccompanied by a student’s true change of heart on their chosen specialty) can suggest that a student prioritized getting their numbers up.

How robust was the analysis? - I don’t expect students to be running full RCTs with run-in periods here, but the use of strong statistical tests among a large cohort suggests students learned a thing or two about good research practice, even if the results of the study are not that important. I would take a student who published 2 demographic-matched, well-controlled cohort studies over one that published 25 correlational analyses.

Publishing Journal - This seems obvious, but should be stated given the rise of predatory journals that many students submit lazy research to in order to hit that 37 number for neurosurgery. Students should be aiming to publish their research in peer-reviewed PubMed-indexed journals and to present their work at state or national-level conferences.

Increasing weight of case report publications - there seems to be a negative view towards case-report writing as a means to resume-pad. I wrote an entire post on why this is wrong and how case report writing actually helps build real-life clinical skills.

In addition, we need to set reasonable expectations for applying students who simply are going to look at that first chart and start freaking out. On the whole, research participation needs to be considered to a much smaller degree than it is now, with an increased emphasis on other aspects of the application, including recommendations, clerkship narrative comments, the personal statement, interview performance, and meaningful extracurriculars.

I am fortunate that I enjoy participating in research in my free time. You can check out the work I have done here. In my view, research should be done to further advance the medical field and is an important task core to our profession as scientists. However, holding these unreasonable publication quotas over our heads as trainees not only fails to accomplish this goal, but it also makes existing problems in medicine, such as diversity and equity, even worse. We have to start thinking about the role of research in medical education using a different framework.